book reviews forevermore

Goodreads refugee and wordpress blogger

“The more I read, the more I acquire, the more certain I am that I know nothing.”

― Voltaire

Fabulous, actually

We Are All Completely Fine is a fabulous, complicated novella about a group of five damaged people and the psychologist who brings them together. Dr. Jan claims she wants to help them, but the five members have been through various supernatural traumas and are accustomed to disbelief when they share their unlikely histories: “Every small group was a chemistry experiment and the procedure was always the same: bring together a group of volatile elements, put them in a tightly enclosed space, and stir. The result was never a stable compound, but sometimes you arrived at something capable of doing hard work, like a poison that killed cancer cells. And sometimes you get a bomb.“

The story becomes almost a character study as we find out more about each person, and the strange situations they’ve survived: “After all, one of the issue we had in common was that we each though we were unique. Not just survivors, but sole survivors. We wore our scars like badges.” But Gregory wisely stays away from historical info-dumping and instead allows their stories to be shared in the course of conversation. As they trust–and challenge–each other, they discover they have more in common than they expected. Shortly after, the pace catapults forward, focusing on immediate danger.

Gregory writes in ways that touch the heart of what it means to be human. He also writes in ways that are horrorific, surprising, and humorous. We Are All Completely Fine is like a psychotherapy text in comic book form, making it accessible and applicable in ways one would have never considered. There are moments that make me squirm, but they are done with such sophistication that Gregory brings me to a place of compassion.

“She believed that people were captains of their own destiny. He agreed, as long as it was understood that every captain was destined to go down with the ship, and there wasn’t a damned thing you could do about it.“

Gregory is fast becoming one of my go-to authors, with stories I can pick up in almost any mood and end up deliciously satisfied. I want something with humor? Here: “And then he wondered what the collective noun was for psychologists: a shortage of shrinks? A confession of counselors?” Or profound: “What the patients didn’t understand was that this was the human condition. The group members’ horrific experiences had not exempted them from existential crises, only exaggerated them.” Or do I need a diverting plot in a genre-bender setting to distract me from my everyday life? Gregory provides that too.

I re-read this today thinking about my review, and was no less entertained or captivated–but I did highlight another handful of lovely phrases. I highly recommend it.

“Also, I might be entertaining the idea of tamping down my nihilism. Just a bit. Not because life is not meaningless–I think that’s inarguable. It’s just that the constant awareness of its pointlessness is exhausting. I wouldn’t mind being oblivious again. I’d love to feel the wind in my face and think, just for a minute, that I’m not going to crash into the rocks.“

Many, many thanks to NetGalley and Tachyon Publications for a review copy, and to Carly for introducing me to Gregory’s works.

Yum.

Pandemonium reminds me of those times when my foodie friends are dragging me to a “fabulous new restaurant” where (mostly) familiar ingredients are deconstructed, spiced and recombined in a creative way. At least this time, instead of an unsettling mess, it resulted in one of those perfect, satisfying meals that fulfill a sensory need as much as a physical one. Not so unusual that I’m left with a disturbing aftertaste, and not so routine that it is immediately forgettable. To wit:

Salvatore’s award-winning pizza with wine-poached fig, bacon and gorgonzola. Unusual but delicious take on pizza. http://salvatorestomatopies.com/2012/08/24/salvatores-wins-the-first-annual-slice-of-sun-prairie-pizza-contest-with-wine-poached-fig-and-local-bacon-pizza/

Pandemonium is a lot like that. Somewhat familiar elements drawn from comic books, buddy flicks and mythology are blended together in a plot that moves quickly but respects each ingredient. Add in some complex characterization, dashes of dark humor and develop it with truly fine writing, and I’m served a book that satisfying on both intellectual and emotional levels.

The simple summary: Del is returning to his mother’s home with a dual purpose: confess a recent car accident and psychiatric hospitalization, and to meet a famous demonology researcher at a national conference. Demons are real, although their manifestations usually pass quickly, while the behavior follows certain archetypes: The Painter, the Little Angel, Truth: “The news tracked them by name, like hurricanes. Most people went their whole lives without seeing one in person. I’ve seen five–six, counting today’s.” When Del was young, he was possessed by the Hellion, a wild boy entity, and Del has recently developed suspicions that the Hellion never left him. The story follows Del as he attempts to understand and perhaps free the entity inside him.

The plot moved nicely with enough balance between introspection and action to keep me interested. What I loved the most, however, was the writing. There’s the vivid imagery:

A small white-haired women glared up at me, mouth agape. She was seventy, seventy-five years old, a small bony face on a striated, skinny neck: bright eyes, sharp nose, and skin intricately webbed from too much sun or wind or cigarettes. She looked like one of those orphaned baby condors that has to be fed by puppets”

the humor:

“The question, then, was how long could a human being stay awake? Keith Richards could party for three days straight, but I wasn’t sure if he counted as a human being“

and sheer cleverness (because I’ve been this lost driving in Canada):

“For the past few hours we’d been twisting and bobbing along two-lane back roads, rollercoastering through pitch-black forests. And now we were lost. Or rather, the world was lost. The GPS told us exactly where we were but had no idea where anything else was.

Permanent Global Position: You Are Here.”

For those who might want a sense of the flavor, I was reminded of American Gods, of George R.R. Martin’s Wild Card world (my review) blended with Mythago Wood (my review), but done much, much better. While I had problems maintaining interest in each of the aforementioned, I had no such challenge with Pandemonium. Each bite revealed something almost familiar but somehow unexpected. There’s a lot to enjoy, and an equal amount to ruminate on after finishing. I’ll be looking for more from Gregory.

Oh yes: a sincere thank you to bookaneer for inviting me to dinner.

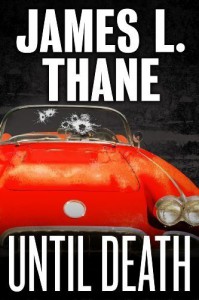

Until Death

I’m not usually a person that keeps track of opening lines, or even pays them particular attention. However, the beginning of Until Death gave me a shiver of anticipation:

“When the meeting finally adjourned at five after nine on a Thursday night, Neal Ballard had twenty-two minutes to live.“

Perfect. The dispassionate language downplays the emotion, but the very phrase “twenty-two minutes to live” ramps it right back up.

I’ve put off reading Until Death because of the awkwardness of reviewing a friend’s work. In an effort at full disclosure, I’ll note I’ve been hanging around James over at ShelfInflicted and on Goodreads for some time. Despite the contact, he’s never offered a copy of the book or requested a review, a reticence I have always appreciated. You see, I tend to be both analytical and honest; more than once, my mouth has landed me in challenging situations. As a matter of fact, I’m currently in trouble for talking in a class, and, no, I am both serious and over forty. Let’s just say my time there is limited. At any rate, I shy away from reviewing friend’s books because I am uncomfortable not being honest, and because I have this drive to review what I read. Whatever. The point is, I hesitated, only trying the book when an Amazon deal came along. I really needn’t have been reluctant; Thane has a gift for writing, evoking images and characters that seem real.

Characters go beyond genre stereotypes. Although they may start at comfortably familiar places, Thane fleshes them out so that they feel unique, real people struggling with negotiating their emotions. For instance, we’re introduced to Detective Sean Richardson in a classic noir situation: “in violation of about fourteen department regulations, I was sitting in the lounge at Voce, working on a second glass of Jameson and listening to the Rachel Eckroth Trio.” Eventually we get to Richardson’s backstory, but by no means does he wear it on his sleeve. His partner, Maggie McClinton, is a classic foul-mouthed spitfire dealing with issues on the home front, but in this case, ‘Issues’ means a pastor boyfriend with children who is seeking greater connection.

Detectives Sean and Maggie catch a case where a man is brutally beaten to death in his garage. Unfortunately, a lack of leads and a plethora of other cases means the Ballard case gradually moves to the back burner. The big break comes the day that Gina Gallagher, a personal trainer, introduces herself to Richardson, hoping to share some crucial information–as long as he doesn’t charge her with prostitution. Gallagher has lost her weekly planner, and both Ballard and another recently dead man were part of her exclusive client list. Suddenly Richardson and McClinton have all sorts of leads to pursue.

Plotting had a number of twists and turns, one of which surprised me. It’s always a pleasure when a mystery writer can avoid telegraphing the solution. My biggest challenge with the story was a few change in perspectives that seemed to be used as a means of building tension. That’s not uncommon in more modern stories–perhaps a sign that authors (and editors?) are catering to reader attention-deficit–but it tends to work against my own preference. In this case, the added perspective was done well enough to add further insight into the characters, not only heightening plot tension. I enjoyed Richardson’s character, particularly his moments at home; the scenes of him listening to jazz while sipping whiskey were so vivid, I felt like I was in the room.

Overall, I recommend it, particularly to fans of J.A. Jance’s Detective J.P. Beaumont. And I won’t be afraid of reading any more of Thane’s books.

Thane’s entertaining interview over at Shelf Inflicted:

http://www.shelfinflicted.com/2013/12/15-questions-with-gentleman-james-thane.html

shoes worth walking in

The Walt Longmire series is proving extremely satisfying, and the fourth book, Another Man’s Moccasins, is no exception.

What keeps me coming back?

The characters: mature throwbacks to Western cowboy mythology with values of independence, loyalty and trust–but without the abundant sexism and racism. Sheriff Walt Longmire is a former Marine, ex-football player and is as faithful as they come, and his brother-in-arms, Henry Running Bear, is normally centered, thoughtful and self-contained. In this book, Walt relives some of their interactions in Vietnam, giving interesting insight into their personalities now and a sense of how they’ve matured.

“I thought about all the wayward memories that had been harassing me lately, the recrimination, doubt, injured pride, guilt, and all the bitterness of the moral debate over a long-dead war. I sat there with the same feeling I’d had in the tunnel when the big Indian had tried to choke me. I was choking now on a returning past that left me uneasy, restless, and unmoored.”

Then there’s the writing, an enjoyable combination of clear prose and vivid imagery:

“The other [photo] was of the same woman seated at a bus station, the kind you see dotting the high plains, usually attached to a Dairy Queen or small cafe. She was seated on a bench with two young children, a boy and a girl. She wore the same smile, but her hair was pulled back in a ponytail in this photo, so her face was not hidden. She looked straight at the camera as she tickled the two children, who looked up with eyes closed and mouths open in laughing ecstasy.“

Vietnam flashbacks are not a reliable strategy for drawing me into a story. I came of age in a period where Hollywood was enthusiastically revisiting the war, finally acknowledging the hardships of the people who fought there. It began with Apocalypse Now and followed by a string of hits (Platoon, Hamburger Hill, Born on the Fourth of July, Full Metal Jacket, The Casualties of War, Jacob’s Ladder, Good Morning Vietnam), so it’s not easy to play to my sympathies–they’ve already been manipulated to the max by Hollywood. Yet the eerie possible connection of Walt’s past experiences there to the current case works well. By the end, I realized Johnson had some very clever parallels between the two story lines. I was also impressed the way Walt revisiting his memories had him questioning his racial biases, as well as giving him unexpected empathy with a suspect.

Why not five stars? Walt was a bit slow to pick up on several things that could have been dealt with by basic investigation; general over-protectiveness about his daughter, which made sense but isn’t really a palatable storyline; and the complicated situation with Vic, who occasionally feels larger than life. Still, those issues pale in comparison to the rest of the read. Truly, it is an enjoyable story that was worth a second read.

Authority. Or lack thereof.

If Annihilation reminded me of Jeanette Winterson’s writing, then Authority reminded me of Kafka, but not the interesting Kafka, one of the boring ones, which surely if I say which one, my dear friends are going to quickly assure me that I’m quite wrong and there is no way Kafka could ever be boring with such Big Ideas. So maybe I don’t mean Kafka. Maybe I mean one of those other stodgy old writers from Advanced English who was clearly writing about the Human Condition in Big Fat Metaphors. Maybe Moby Dick. Is it safe to call Moby Dick boring? It also reminded me a little of Joseph Heller, in Something Happened, when, of course, nothing does happen. Or Waiting for Godot, only more like Waiting for Area X. Or maybe I’m thinking of that movie Brazil, which is what I always think of when I think of big, boring films about Meaning of Corporations. Which is probably not what Brazil is even about, but you’ll never get me to watch it again, so it doesn’t matter. In my mind, it’s always about a faceless bureaucracy. Anyway, just think of some story from your memory of something that was well-done, full of Deep Meaning about the Human Condition, with a confused narrator, a whole lot of navel-gazing about Ineffectual Man, and you’ll about have it.

Authority is clearly the next side to the prism that composes the Southern Reach Trilogy, but this installment is focused a new character, government official John Rodriguez. He’s been transferred in as replacement of the missing Director of the Southern Reach. In keeping with the tradition of roles superceding names, John adopts a childhood moniker ‘Control.’ His arrival occurs shortly after the Biologist and her team has returned to the Reach (!) sans memories and missing the psychologist. As Control seeks to puzzle out the mystery of the Biologist and the Reach, he also faces interagency status conflicts, with antagonism from the Voice above as well as from below, in the form of Assistant Director Grace:

“But Control preferred to think of her as neither patience nor grace. He preferred to think of her as an abstraction if not an obstruction. She had made him sit through an old orientation video about Area X, must have known it would be basic and out of date. She had already made clear that theirs would be a relationship based on animosity. From her side, at least.“

Maybe the transfer is a plot to get rid of him. Maybe its a plot his mother has to advance his career. Maybe it’s just the only job available to a man who compromised his cases. It is hard for both the reader and Control to tell, and honestly, I don’t know that I cared. He’s not an anti-hero, just an everyday bureaucrat trying to do the best he can and survive complex corporate politics. And complex family politics. ‘Control’ is clearly an irony for a man who has none.

We experience the rotting-honey smell of the Reach (!) through the new eyes of Control, as he almost but-not-quite bonds with both the Biologist held in isolation and the ghost of the former Director (I’m not spoiling anything; I’m not being literal here, people. I think). If I enjoyed Craig Johnson‘s show-don’t tell mysteries, this is pretty much the opposite; not a lot happens except in Control’s head, with a few bizarre incidents spurring him onward.

But the writing! I love the writing, so vivid and clever and allegorical, except that almost every little bit is vivid and clever and allegorical so it really does need a bit of a driver to engage my emotions:

“Before he’d arrived, Control had imagined himself flying free above the Southern Reach, swooping down from some remote perch to manage things. That wasn’t going to happen. Already his wings were burning up and he felt more like some ponderous moaning creature trapped in the mire.“

Remember the swamp creature from Annihilation? Of course you do! What does it mean? Is Area X is the Reach, and the Reach is Area X? Maybe. I don’t know, and am not entirely sure I care. Enough navel-gazing, Control.

Much like Zone One, Colin Whitehead’s brush with zombie Metaphorical Fiction, this book missing the five star despite truly excellent writing, purely out of personal taste and enjoyment. Well written, well-crafted, I read it because I’d like to see Vandermeer’s gestalt, as well as know more about Area X. Onward!

14

14

I loved researching and writing ethnographies in anthropology class; the idea of describing cultural norms in the hopes of understanding as well as to speculating on their function in society. A study of a culture’s biology, if you will. Aliette de Bodard’s series Obsidian and Blood (Bodard’s site) reminds me of an ethnography, but instead of the dry, pseudo-scientific tone discussing a culture in general, Bodard gives us the personal perspective of Acatl, High Priest of the Dead, as he seeks to protect his country from the fallout of a leader’s death. It’s the best kind of cultural story-telling, immersing me in a time and I place I can barely imagine and yet offering non-judgemental insight on ways of thinking and ancient lives.

It begins as the Mexica (Aztec) Empire is undergoing a period of political change. The Speaker, the leader of the Empire, is the link between the Hummingbird God and the people of the Empire. But the Speaker is at the end of his life and his death will break that bond, allowing the star demons and other malevolent gods to intrude into the Empire. The Empire’s only hope is to quickly choose and invest another Speaker, but unfortunately, Council politics stand and power games in the way of a quick decision. When a low-ranking member of the Council is brutally murdered, Acatl, the High Priest of the Dead, knows that this is only the first of many deaths to come.

Aztec calendar stone. http://kids.britannica.com/comptons/art-174883/This-ancient-relic-of-the-Aztec-calendar-shows-the-sun

Characterization is fabulous, with complicated dynamics between characters impacted by character growth. Teomitl, brother to one of the candidates for Speaker, has been Acatl’s apprentice for some time now, and it might be time for Acatl to let him find his own path. There are a variety of adversaries, each providing a different kind of dynamic. There are the star demons and various gods who would like to see the Empire end so that they can take power in their own hands. Then there are the Council members, who may want the good of the Empire–if they get power in it. Their faith in the relationship to the gods may be tenuous at best, so they aren’t as motivated as Acatl to protect the people from the star demons. As Acatl meets each member, the reader gets a sense of a wide variety of motivations in the Council.

Plotting was enjoyable. I found it adequately complex, nicely balancing the spiritual with the corporeal. I tend to get annoyed by dream-walk type segments and appreciated how Bodard balanced the spiritual experience of traveling to the spirit worlds with that of the Fifth World (the one the Aztecs live in). It was one of the most interesting aspects to the writing, the complexity of the situation facing Acatl and his constraints both physical and spiritual.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this series is that by the end, I’m not entirely sure about the supernatural aspects. Apparently, there was a major eclipse about the time this story was set. I don’t doubt that the members of the real Empire believed in the gods and demons to greater or lesser extent, just as they did in the book. But I find myself wondering if the experiences with the gods in the story were ‘real’ or just their interpretation of phenomena, along with dream states/visions. In the end, I don’t know that it matters, but it says a great deal that one can walk away from a ‘fantasy’ book with that sense of possibility. In this way, Bodard did come close to an ethnography, helping the reader understand and interpret the experience the way a member of the culture does.

I enjoyed this one even more than the first. Perhaps it is because I’m a little more comfortable in Bodar’s Mexica past. I’m not even sure what one would name this strange mix of historical, mystery, and fantastical. I just know that it’s a very satisfying read; if you are looking for a different take on a fantasy mystery, the Obsidian and Blood series is a great place to begin.

Drawing of Tenochtitlan, from U.Minnesota-Duluth

Drawing of Tenochtitlan, from U.Minnesota-Duluth

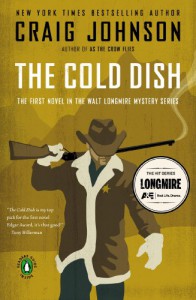

Delicious

I knew in the first four pages that I was going to enjoy this book.

It begins with Sheriff Walt Longmire of Absaroka County, Wyoming, sitting in his office, watching the geese fly south. Ruby, dispatcher/receptionist, interrupts his musings to tell him he has a call from Bob Barnes, who wants to report a dead body he discovered when he and his son went to collect their sheep.

“She leaned against the doorjamb and went to shorthand, ‘Bob Barnes, dead body, line one.’

I looked at the blinking red light on my desk and wondered vaguely if there was a way I could get out of this.

‘Did he sound drunk?’

‘I am not aware that I’ve ever heard him sound sober….‘

‘Hey Bob. What’s up?’

‘Hey, Walt. You ain’t gonna believe this shit…’ He didn’t sound particularly drunk, but Bob’s a professional, so you never can tell.“

He takes the report from Bob, verifies the information on the phone with Billy, Bob’s equally drunk son, and just as he’s about to hang up,

“‘Yes sir… Hey, Shuuriff?’ I waited. ‘Dad says for you to bring beer, we’re almost out.’“

Walt tells Ruby “that if anybody else called about dead bodies, we had already filled the quota for a Friday and they should call back next week,” and heads to his car. He swings by the drive-through liquor store, and on his way out of town, passes by one of his deputies who is seriously irritated with traffic detail and delegates the job to her instead.

This is no ordinary sheriff, and this is no ordinary gunslinger book. Sheriff Walt has lived a hard fifty years, most of it in the immediate area, unless you count college in California and those years in Vietnam. His best friend is another Vietnam vet, a local Cheyenne Indian, Henry Standing Bear. Walt’s voice is dry, humorous, self-depreciating, and more than a little depressed. He’s also more than a little obsessed with the rape of a Cheyenne girl, a case that has been bothering him for the last three years. Unlike the typical detective haunted by an unsolved case, Walt caught the guilty parties, but justice wasn’t handed out for a variety of social and political reasons. When the body Bob finds turns out to be one of the lead defendants, Walt suspects someone is out for revenge, possibly even Henry.

Like many mystery investigators, Walt is emotionally wounded, carrying grief from his wife’s death three years earlier. Henry has had enough and believes its time to encourage–or kick–Walt out of his rut, and Walt finds personal motivation when a beautiful local woman, Vonnie, flirts with him. As much as it is a story about a murder, it is also a story about Walt and his friendship with Henry, as well as small town dynamics and the complex relationships that hold people together.

The characters feel human, and even brief appearances feel nicely developed. I enjoyed the acidic, opinionated Ruby, Walt’s two deputies, Vic and Turk, each going through their own challenges. The idiotic over-confident twins were enough to make Walt and me long to shoot them. The lingering sadness of the Cheyenne girl’s father, Lonnie, and his admittance of human frailty along with his laughable speech patterns made him one of the more moving characters. The prior sheriff, Lucian, comes out of retirement from assisted living to give Walt a hand, and while he adds some politically incorrect spice, he’s somewhat redeemed through his honesty and honor. I also appreciate that women appear in many different roles in this book, as friends, fellow professionals, love interests. It’s a nice change from the mysteries where women show up only as victim/love interest.

There’s nice moments of humor threaded through this book. Most of it comes from Walt’s dry law enforcement humor, the kind that is meant to keep the devils at bay more than mock others. He reflects at the death scene, where the dead body has been lying, examined and nibbled by a flock of sheep,

“Yea, verily, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will live forever. If I don’t, I sure as hell won’t become an unattended death in the state of Wyoming with sheep shit all over me.”

Then there’s Al, providing some much-needed comic relief for the reader–and for Walt–at a particularly tense moment:

“There was a halfhearted attempt at a Tiki theme with native paintings of naked women and carved wooden sculptures as decoration. The most amazing stacks of magazines and catalogs towered against the walls; National Geographic and American Rifleman made up the visible majority. It was like being in the dead letter office on Fiji.”“

Writing is pleasantly sophisticated for the genre, and nice mix of dialogue and description. While Walt and Henry may make Lone Range references, they also reference Steinbeck, Shakespeare and even throw in a little French. For those who enjoy it, there’s also a fair bit of local history mixed in, particularly relating to General Custer and the Sharps gun. Most of the violence occurs off-scene, and is not particularly gory. Thriller elements come late in the story. There’s some semi-mystical elements that I found interesting, creating a strange parallel to my most recent read, Harbinger of the Storm, about a priest and his search for killers, both corporeal and supernatural. It cemented my feeling that this case was about Walt more than Melisaa; his need for resolution, his need to move on; his need for trustworthy friends. The spiritualism added moments of moving imagery to an already emotionally complex book.

I’m looking forward to checking out the next book and seeing where Walt is headed.

'Til the World Ends. Or hopefully, sooner.

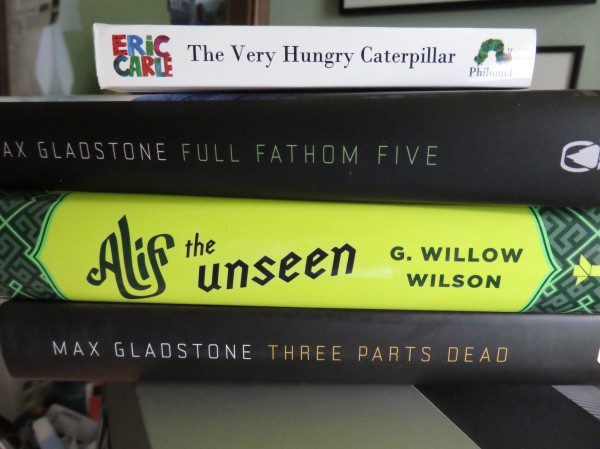

Labor Day Weekend and Half-Price Books 20% off sale were completely irresistible.

Really. I couldn’t.

So I headed over and found a few books I knew were delightful and one I thought may be interesting:

Just guess which one was the dud.

Here, let me help you:

Death of the Necromancer review: http://clsiewert.wordpress.com/2013/0…

The Shadowed Sun review: http://clsiewert.wordpress.com/2013/0…

Review for Retribution Falls: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show…

But I’m a fan of the apocalypse genre, and I’ve heard both Aguirre and Kagawa’s names for quite a while. And, I often enjoy short stories/novellas. And, sale!, right?

Wrong.

Dawn of Eden, by Julie Kagawa: A woman running one of the last open clinics for victims of the Red Lung disease takes in two strangers, one of which has the disease. Unfortunately, his disease has mutated, spreading like wildfire among the already dead. The handsome living stranger, Ben, soon convinces Kylie they need to abandon the clinic and head to his estranged childhood home at a ranch in Illinois.

Overall, I was disappointed in the writing. It was acceptable, if slightly slightly flat. Plotting was completely predictable. A vaguely interesting disease premise/world-building was severely hampered by super-tropey characters that may indeed be deemed Too Stupid To Live. Alas, they do: apparently it is a prequel to one of her more popular series.

Thistle & Thorne by Ann Aguirre: A woman in the slums has a job forced upon her by the local gang-leader. Although it is a set-up, she becomes the excuse for a brutal takeover campaign.

This was the standout in the collection. Just enough bones of some interesting world-building, decent plotting, and somewhat standard characters that actually have some depth to them. Slight beginnings of a romance that did not in any way interfere with problem resolution.

Sun Storm by Karen Duvall: yet another woman working at a hospital (sigh) in exchange for her demented father’s care. She’s a Deviant, a person who has been exposed to the devastating sun-showers and lived, developing a super-power. She meets Ian outside the hospital, and he tags along as she goes on a run to warn a nearby town of an incoming storm.

A meh, although it might appeal to fans of superheros and Rachael Cline’s weather-related UF. Characterization is an inconsistent mess. Interesting world-building. Amazingly bad dialogue.

Truly, I’d advise a pass, unless you are a fan of any of the authors. It did convince me that Aguirre will likely be worth checking out further, while Kagawa won’t.

Shhh. Secrets.

Here’s how I imagine it went down:

French and her besties are at their high school reunion weekend. They’re sitting around drinking wine and reminiscing when someone decides to pull out the old ouija board from the attic storage. Much to their surprise, they channel Agatha Christie’s voice from Cat Among the Pigeons. Flush with success, they try again, and discover Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes (review here).

Alright; maybe I just have my own upcoming reunion on my mind. But I was captivated by the way The Secret Place integrated the turbulent days of youth at a girls’ boarding school with a murder investigation by Dublin’s finest, proving again that French has talent in spades. If there is one thing her prior four books in the Murder Squad series have made clear, French is great at character creation. And atmosphere. Oh, and dialogue. Okay, fine; she’s good at all the components that make a book enjoyable. This time she’s also nailed the police procedural aspects of the case.

The story begins with Holly and her three friends hanging at a playground, musing on the end of summer and their upcoming year together at boarding school. Fast forward to Detective Stephen Moran at the Cold Cases Unit. Holly appears at the police station requesting a meeting with him, six years after when they last met in events covered by The Faithful Place. The exclusive boarding school she resides at has a noticeboard where students can put up anonymous confessions. Holly has found a postcard with an old picture of murder victim Chris Harper. The words “I know who killed him” are pasted across in cut-out letters. Moran seizes the opportunity to wedge his foot in the door of the Murder Squad, and personally takes the note to the case’s lead detective, Antoinette Conway. As she is currently without a partner, he offers her the benefit of his disarming interview skills when she returns to the school to re-interview the students. What follows is an exploration of what led to the death and how the detectives retroactively piece the story together.

The plot timeline is unusual, as it combines the current investigation with viewpoints from the girls and from Chris during the prior year. The investigation takes place within one incredibly busy day, while the events in the girls’ lives cover the entire previous year at school. It’s an interesting kind of time shifting for a murder mystery, but I came to enjoy it. Instead of learning about the prior relationships and circumstances through flashbacks, we live it with four of the girls and the victim, bringing a heightened sense of doom to their daily lives.

Characterization is stellar. The introduction to Murder Squad Detective Conway:

“Antoinette Conway came in with a handful of paper, slammed the door with her elbow. Headed for her desk. Still that stride, keep up or fuck off… Just crossing that squad room, she said You want to make something of it? half a dozen ways.“

Or the (re-) introduction of Detective Frank Mackey:

“I know Holly’s da, a bit. Frank Mackey, Undercover. You go at him straight, he’ll dodge and come in sideways; you go at him sideways, he’ll charge head down.“

Marvelous, really; contrast that with the books that focus on the appearance of the character first, or contain long soliloquies where the character helpfully identifies their history and preferences. In the prior examples, French distills two very different personalities into brief thoughts, so that when we finally meet them, dialogue can be focused and snappy, but still shaded with the layers of meaning from knowing the character. It is a beautiful technique that mirrors real life; if you follow me through my day, I don’t muse on each person interact with; rather, our interactions are defined partially by our history and word choice describing it would reflect it. French’s writing captures that shading without huge, potentially distracting expository swathes.

One of the aspects I enjoyed most was the delicate balance between Moran and Conway. As her fierce personality is evident from the start, I was fascinated by Conway’s attempt to develop a working relationship with her. Initially, Moran is ingratiating himself out of expedience, but it becomes clear Conway understands his intentions. French does a nice job of keeping both Moran and the reader off-balance, guessing at what Conway thinks while having a sense of where it is going.

The setting is immersive, bringing back memories of adolescence in all its insecurities:

“Two years on, though, Becca still hates the Court. She hates the way you’re watched every second from every angle, eyes swarming over you like bugs, digging and gnawing, always a clutch of girls checking out your top or a huddle of guys checking out your whatever. No one ever stays still, at the Court, everyone’s constantly twisting and head-flicking, watching for the watchers, trying for the coolest pose.“

and glories:

“Darkness, and a million stars, and silence. The silence is too big for any of them to burst, so they don’t talk. They lie on the grass and feel their own moving breath and blood… Selena was right: this is nothing like the thrill of necking vodka or taking the piss out of Sister Ignatius… This is nothing to do with what anyone else in all the world would approve or forbid. This is all their own.“

It is worth noting for those who are new to French that while The Dublin Murder Squad is nominally a series, the connection is through the web of relationships in the police department. Each story tends to focus on a particular member of the squad and their emotional entanglement to the case at hand. Although they may reference events in a prior story, they usually aren’t spoilerish, nor is reading them in order needful. In this case, French seems to draw back from a detective’s emotional dissolution and instead focus on a more positive resolution.

I found The Secret Place to be a complex, satisfying story, delicately balanced between mystery and character story. There was no part that I was even considered skimming, as the flashbacks held as much interest as the police procedural. In fact, reviewing was a challenge, as I kept thumbing through my notes, tempted by my saved passages to re-read. Though I read an advance copy, I suspect this is one I’ll have to add to the paper library.

Many thanks to NetGalley and Viking for providing me an advance copy to review. Quotes are taken from a galley copy and are subject to change in the published edition. Still, I think it gives a flavor of the magical writing.

Shhh. Secrets.

Here’s how I imagine it went down:

French and her besties are at their high school reunion weekend. They’re sitting around drinking wine and reminiscing when someone decides to pull out the old ouija board from the attic storage. Much to their surprise, they channel Agatha Christie’s voice from Cat Among the Pigeons. Flush with success, they try again, and discover Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes (review here).

Alright; maybe I just have my own upcoming reunion on my mind. But I was captivated by the way The Secret Place integrated the turbulent days of youth at a girls’ boarding school with a murder investigation by Dublin’s finest, proving again that French has talent in spades. If there is one thing her prior four books in the Murder Squad series have made clear, French is great at character creation. And atmosphere. Oh, and dialogue. Okay, fine; she’s good at all the components that make a book enjoyable. This time she’s also nailed the police procedural aspects of the case.

The story begins with Holly and her three friends hanging at a playground, musing on the end of summer and their upcoming year together at boarding school. Fast forward to Detective Stephen Moran at the Cold Cases Unit. Holly appears at the police station requesting a meeting with him, six years after when they last met in events covered by The Faithful Place. The exclusive boarding school she resides at has a noticeboard where students can put up anonymous confessions. Holly has found a postcard with an old picture of murder victim Chris Harper. The words “I know who killed him” are pasted across in cut-out letters. Moran seizes the opportunity to wedge his foot in the door of the Murder Squad, and personally takes the note to the case’s lead detective, Antoinette Conway. As she is currently without a partner, he offers her the benefit of his disarming interview skills when she returns to the school to re-interview the students. What follows is an exploration of what led to the death and how the detectives retroactively piece the story together.

The plot timeline is unusual, as it combines the current investigation with viewpoints from the girls and from Chris during the prior year. The investigation takes place within one incredibly busy day, while the events in the girls’ lives cover the entire previous year at school. It’s an interesting kind of time shifting for a murder mystery, but I came to enjoy it. Instead of learning about the prior relationships and circumstances through flashbacks, we live it with four of the girls and the victim, bringing a heightened sense of doom to their daily lives.

Characterization is stellar. The introduction to Murder Squad Detective Conway:

“Antoinette Conway came in with a handful of paper, slammed the door with her elbow. Headed for her desk. Still that stride, keep up or fuck off… Just crossing that squad room, she said You want to make something of it? half a dozen ways.“

Or the (re-) introduction of Detective Frank Mackey:

“I know Holly’s da, a bit. Frank Macket, Undercover. You go at him straight, he’ll dodge and come in sideways; you go at him sideways, he’ll charge head down.“

Marvelous, really; contrast that with the books that focus on the appearance of the character first, or contain long soliloquies where the character helpfully identifies their history and preferences. In the prior examples, French distills two very different personalities into brief thoughts, so that when we finally meet them, dialogue can be focused and snappy, but still shaded with the layers of meaning from knowing the character. It is a beautiful technique that mirrors real life; if you follow me through my day, I don’t muse on each person interact with; rather, our interactions are defined partially by our history and word choice describing it would reflect it. French’s writing captures that shading without huge, potentially distracting expository swathes.

One of the aspects I enjoyed most was the delicate balance between Moran and Conway. As her fierce personality is evident from the start, I was fascinated by Conway’s attempt to develop a working relationship with her. Initially, Moran is ingratiating himself out of expedience, but it becomes clear Conway understands his intentions. French does a nice job of keeping both Moran and the reader off-balance, guessing at what Conway thinks while having a sense of where it is going.

The setting is immersive, bringing back memories of adolescence in all its insecurities:

“Two years on, though, Becca still hates the Court. She hates the way you’re watched every second from every angle, eyes swarming over you like bugs, digging and gnawing, always a clutch of girls checking out your top or a huddle of guys checking out your whatever. No one ever stays still, at the Court, everyone’s constantly twisting and head-flicking, watching for the watchers, trying for the coolest pose.“

and glories:

“Darkness, and a million stars, and silence. The silence is too big for any of them to burst, so they don’t talk. They lie on the grass and feel their own moving breath and blood… Selena was right: this is nothing like the thrill of necking vodka or taking the piss out of Sister Ignatius… This is nothing to do with what anyone else in all the world would approve or forbid. This is all their own.“

It is worth noting for those who are new to French that while The Dublin Murder Squad is nominally a series, the connection is through the web of relationships in the police department. Each story tends to focus on a particular member of the squad and their emotional entanglement to the case at hand. Although they may reference events in a prior story, they usually aren’t spoilerish, nor is reading them in order needful. In this case, French seems to draw back from a detective’s emotional dissolution and instead focus on a more positive resolution.

I found The Secret Place to be a complex, satisfying story, delicately balanced between mystery and character story. There was no part that I was even considered skimming, as the flashbacks held as much interest as the police procedural. In fact, reviewing was a challenge, as I kept thumbing through my notes, tempted by my saved passages to re-read. Though I read an advance copy, I suspect this is one I’ll have to add to the paper library.

Many thanks to NetGalley and Viking for providing me an advance copy to review. Quotes are taken from a galley copy and are subject to change in the published edition. Still, I think it gives a flavor of the magical writing.

9

9

A gift? For me?

One mark of a great book is how it plays with reader expectations. The strategy of taking a conventional genre story and turning it sideways often works. Sometimes it can fail, coming across as little more than a clever gimmick. But sometimes it succeeds beyond imagining, particularly in the hands of an author with talent like Carey’s. The Girl With All the Gifts uses lovely prose to explore the growth of ten year old Melanie, a child of the apocalypse who seems to be shuttled between a cell, a classroom and a shower.

It is a story about discovery. Melanie is particularly fond of Miss Justineau, a teacher who exposes them to wonderful ideas: Greek stories and mythology, playing a flute, the kings and queens of England, and even the population of all the British cities (allowing her to figure probable population density, though she has the feeling her figures need updating). The day they read the Light Brigade (presumably The Charge of the Light Brigade) and start asking Miss Justineau about death, and families, ideas start sparking:

“Melanie knows her classmates well enough to be sure that they’re turning Miss Justineau’s words over and over in their minds, the same way she is–shaking them and worrying at them, to see what insights might fall out. Because the one thing they never learn about, really, is themselves.“

It is a story about a innocence. We learn about Melanie the same way that she does; in bits and pieces as she assembles the puzzle of her world around her. Her day always begins in her cell, with Melanie sitting in a wheelchair, waiting for the Sergeant to point his gun at her while his two soldiers buckle straps around her wrists, ankles and neck. She’s wheeled into a classroom with other kids who appear to be similarly restrained. As Melanie describes her teacher, the facility, the relationships around her, both she and the reader start to build the world. Perhaps the reader will draw inferences faster than Melanie, being older, more experienced, and more cynical. An interesting tension is created as the reader waits to see if her conclusions are correct.

It is a story of contrasts. In the beginning, the austerity of the cells and the barrenness of the compound are countered in the moments Melanie is exposed to the outdoor world. Early on, when Miss Justineau brings spring flowers into the classroom for the first time: “The children are hypnotised. It’s spring in the classroom. It’s equinox, with the world balanced between winter and summer, life and death, like a spinning ball balanced on the tip of someone’s finger.”

It is also a story of identity. Narrative is largely Melanie’s experience, but there are also chances to experience the world from the perspectives of Miss Justineau, Sergeant Parks and Dr. Caldwell. The characters come to discover and learn to define themselves, leading to moments of profound awareness:

“The second is that some things become true simply by being spoken. When she said to the little girl ‘I’m here for you’, the architecture of her mind, her definition of herself, shifted and reconfigured around that statement. She became committed, or maybe just acknowledged a commitment. It has nothing to do with guilt for earlier crimes (although she has a pretty fair understanding of what she deserves), or any hope of redemption. It’s just the outermost point on an arc. She’s risen as far as she can, and now she’s falling again, no longer in control (if she ever was to start with) of her own movements.”

Yet despite the engrossing story, I have, perhaps, two issues with the book. First, Melanie’s voice feels mature, even though it lacks sophistication in interpretation. I’m not a giant fan of books starring a young protagonist, so while it is hard to precisely identify the source of discontent, I feel fairly certain it is there. Secondly, the ending was not precisely satisfying. However, I’m willing to give Carey that one; after all; it was appropriate as well as consistent with his genre-challenge. And some times, the best books push just enough that I am led to my own self-discovery.

I’ve never made any secret of being a zombie apocalypse fan. In my old age, I’m finally allowing myself to be unabashedly enthusiastic. The Girl with All the Gifts is one of those rare genre entries that will satisfy most readers regardless of their feelings about zombie books.

“And then like Pandora, opening the great big box of the world and not being afraid, not even caring whether what’s inside is good or bad. Because it’s both. Everything is always both.

But you have to open it to find that out.“

Thanks to NetGalley and Orbit Books for providing me an advance e-reader copy. Quotes are taken from a galley copy and are subject to change in the published edition.

Shadows are people too.

Once you’ve been to a world filled with magic, what happens next?

September first visited Fairyland in The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making. Young, carefree and heartless: her adventures there exposed to her wonders and dangers; she formed new friendships with barely a thought for home. Now September is back in Omaha, Nebraska, at the end of a very long, non-Fairyland year. It’s been tough; though she has a secret she carries “with her like a pair of rich gloves, which, when she was cold, she could take out and slip on to remember the warmth of days gone by,” she is more ostracized than ever by her classmates. Even worse: her shadow is still missing, left in Fairyland, and her father remains away at war in France. Like most storybook heroines returned to the real world, she has hopes of returning to a land of magic: “being quite a practical child, she had become very interested in mythology since her exploits on the other side of the world, studying up on the ways of fairies and old gods and hereditary monarchs and other magical folk.” (See what Valente does there? Clever, clever!)

But September is under a very large misconception about magical journeys. She assumes that since the dictatorial Marquess is no longer the ruler in Fairyland, her return will mean only joyful reunions, not questing or testing. But how wrong she is, because her missing shadow has grown into herself and become quite wild–she’s appointed herself the Leader of Fairyland Below, and taken a new name: “‘Halloween, the Hollow Queen, Princess of Doing What you Please, and Night’s Best Girl.” The Wyverary stopped. ‘Why, she’s you, September. The shadow the Glashtyn took down below.“” Even worse, now other shadows are going missing and it may be Halloween who is to blame.

When September finally makes it to Fairyland and is–in a sense–reunited with her friends the Wyvern and the Marid, she’s actually reunited with their shadow-selves–so very different than the friends she knew. Even more significantly, she’s a year older and now a teenager, so her heart has done some growing since she was last in Fairyland. More risk and more conflict: “For though, as we have said, all children are heartless, this is not precisely true of teenagers. Teenage hearts are raw and new, fast and fierce, and they do not know their own strength. Neither do they know reason or restraint, and if you want to know the truth, a goodly number of grown up hearts never learn it.“

And there’s the crux of both the beauty and difficulty of Valente’s story: September’s wondrous journey through Fairyland Below is edged with sadness and loss about our shadow-selves and the dark, wanting pieces of ourselves we don’t always acknowledge. September’s missing companions, the question of her shadow-self’s freedom, even the visual dimness of the setting reinforce the sense that there are many sides to a story. The whimsy is still there, but it is an adult-edged whimsy, where reindeer are worried about being caught by (marriage) hunters, kangaroos mine jewels for/of their memories and the Alleyman sieves the shadows from Fairyland.

“‘No one said this was a bad place,’ she told herself. ‘No one said the bottom of the world was somewhere terrible. It’s only dark, and dark’s not so frightening. Everything’s dark in Fairyland-Below. That doesn’t mean it’s wicked.‘”

Because of the complexity and challenge of the message–a different version of growing up, if you will, more like a type of growing out and understanding–I’m not entirely sure Valente’s whimsical tone and imagery works quite as well for me as the first one did. Or, perhaps it does, and really, I’m just not as comfortable with the message. It’s hard to tell.

Stylistically, it is worth noting (again, as always) that Valente is a superb writer. I recently picked up another young-adult book by a writer who has wonderful adult works, and I was struck by how simple both the structure and language were. The Girl series doesn’t oversimplify for its readers; it will challenge and please at any age. This is the type of book whose color blooms as the reader ages, one that can be read at nine, fifteen and twenty-eight, and find it enjoyable each time. Highly recommended to fans of playful imagery, sophisticated prose and small diamond bits of hard truth hidden by shadows.

16

16

Word help

Bookies~

what's the word that refers to a collection of various sayings, quotes, excerpts and the like, bound together in journal-like format? Something like an artist's folio, only word focused.

6

6