book reviews forevermore

Goodreads refugee and wordpress blogger

“The more I read, the more I acquire, the more certain I am that I know nothing.”

― Voltaire

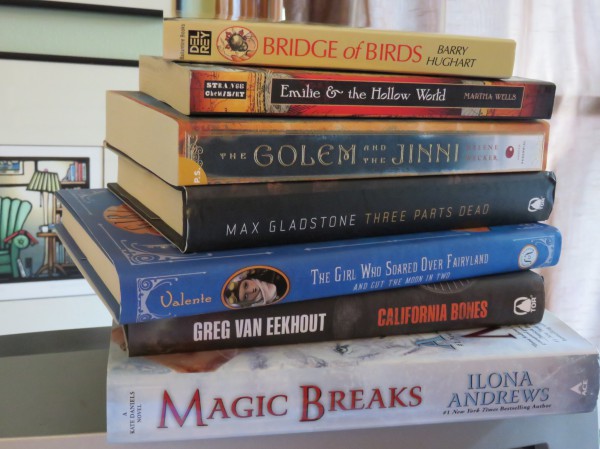

The joy of anticipation: after waiting a few months to spend anything more than 2.99 on a book, I went on an August splurge. This is how I know I'm addicted. I'm sure you can relate.

WTF. Srsly.

If you are willing to gloss over ethical and character problems in a significant character relationship, it might theoretically be an entertaining read.

Seriously, Block. What's the author of the finely tuned Matt Scudder mysteries thinking? Please tell me this was subbed out to a ghost writer, because your introduction of the Barbara Creely character is awful.

Burglar stared off promising, with a unique voice compared to Block's other works, and with a man who clearly enjoyed his illegal activities, even as he was aware of how problematic they were.

Bernie Rodenbarr is set up to be a somewhat loveable anti-hero, the classic criminal with ethics (he only steals from the rich, etc, etc), and it mostly works, until he's under the bed at a woman's house as she is about to get date-raped. And he just hides there and listens, because he's essentially afraid of harm from the rapist. Although I appreciate that Bernie is sharing an honest reason, it had a significant downgrading on my enjoyment level. After the rapist finishes, he further violates her by tossing the apartment looking for money and valuables. He threatens to degrade the unconscious woman further, but is luckily stopped by circumstance. Bernie feels sorry for the woman and makes an effort to "clean up" the mess the rapist/robber made by putting things back, replacing money in her wallet, flushing the condom, etc. Kind, I suppose. But how fucking obtuse: I know what will solve the problem! Let me erase it for you and we'll pretend it never happened!

Later, Bernie goes back to the neighborhood and hangs out at a bar that seems like the woman's type, hoping to run into her. To see if she's okay? Nice thought, but no. To try and warn her that her she needs to start playing it safer? Wow, you're kind of a Pollyanna, aren't you?

No, he meets her, they have a creepy conversation about how it seems they've been "emotionally intimate" before, he goes home with her that night, and spends the night having sex.

Oh, not so he's a stalker or anything--he's friendly and doesn't use roofies, which makes all the difference.

Then, within a week, he's telling her the truth about his occupation... and how he first met her. And you know what? She's okay with it.

What

the

fuck?

The self-disclosure is literally taken care of in a couple of paragraphs. This is despite Bernie earlier reflecting on a conversation with his friend Carolyn about how merely feeling burgled felt like a violation. He tells Barbara she's been roofied and date-raped, along with being robbed. Her reaction? She swears for a minute and then focuses on which window Bernie was going to use to escape.

I will say it again:

What

the

fuck?

Add in a shitload of coincidences, which Bernie self-references twenty times if he does it once, and the ridiculous Hercule Poirot denouement, and I'm left with the uncomfortable feeling that this is a spoof. In which rape is how you meet your next date.

Need I say it again?

Pulpy fun

Don’t you have those days when your brain just needs a break? I’ve been swamped this summer by the seriously un-fun Understanding Pathophysiology. After reading four or five chapters a week, there’s times when my brain craves a bit of shut-off, but my body isn’t ready to sleep. That’s what television is for, right? And sports? But honestly, I’d rather read about silly people and needless danger than watch it, and that’s where Martin’s Unhuman series with Inspector Hobbes fits in. Well, Inspector Hobbes isn’t senseless so much as Andy Caplet is, the diffident reporter assigned to follow Hobbes. Think Sherlock Holmes with slightly more bestial tendencies and Lou Costello as Watson. Think modern English town with supernatural beings just trying to live their lives without harassment, whether its chomping on old bones or standing in a field thinking trollish thoughts. Think–dare I say it–puns.

Andy Caplet is a struggling reporter unexpectedly assigned to follow Inspector Hobbes, one of the fearsome successes of the local police force. The assignment is surprising as Andy’s most notable story to date was his unsuccessful attempt to do a piece on a show-winning hamster, resulting in nasty bite and an unflattering bit of press. Hobbes is focused an unlikely series of events relating to Mr. Roman, whose house was burgled, a violin stolen, and Mr. Roman subsequently found dead, apparently a suicide. When Andy follows Hobbes to the cemetery where Mr. Roman was found, he discovers a newly-opened grave and is almost victim to a ghoulish cover-up. It is the beginning of Andy’s introduction to the unhumans around him, and he decides to stick with Hobbes in hopes of an award-winning story. Perhaps even a book!

The basic premise of Inspector Hobbes is done well. The unfortunate Andy contrasts nicely to the enigmatic, powerful and intelligent Hobbes. Plotting moves quickly from event to event, establishing interesting characters along the way. Particularly entertaining was Mrs. Goodfellow, Hobbes’ live-in cook, housekeeper and friend, with her dental obsession and her tendency to tread quietly. I appreciated the the way Martin hints to the reader and Andy that something about certain characters may not be quite human, a much more enjoyable type of character development than the long-winded info-dump. Hobbes, of course, is the biggest mystery of all–what is he, exactly? And does it matter?

“In truth, and in his own way, he’d looked after me. He was an enigma. He was a monster. He was a policeman. He was someone I out to be writing about.“

Andy, being more of the anti-hero type, frequently leaps to the wrong conclusion, misleading himself and the reader. Although bumbling, he isn’t quite incompetent, and is sincere, so I found him more tolerable than in the second book, Inspector Hobbes and the Curse.

One of the few problems I had with the writing was what appears to me as a tendency to run-on sentences and excessive commas. It could just be my personal fondness for semi-colons and colons showing, but I did find it initially distracting. I think as the action picks up, the commas diminish–or else my mental filter blotted them out. An early example:

“As I landed and turned around, the magazine fluttering to the carpet like a dying pigeon, the blood pounding through my skull, my shin bruised from a sharp encounter with the table, the old lady, standing by the sofa, gave me a gummy smile. Though I coulgh have sworn she did not have a single tooth left in her head, I thought a positive response was appropriate.“

As a side note, although I love paper books, this might be one to read on e-reader. Martin has a tendency to sprinkle a number of English idioms–and by English, I mean country-cultural specific words. And, speaking of abuse of the English language, there’s a story about Hobbes’ stuffed grizzly bear:

“The bus knocked him into a music shop, where his muzzle became entangled in an antique stringed instrument that suffocated him. And so my sad tale ends, with a bear-faced lyre.“

It was fun and entertaining–and didn’t mention molecular biology once. A perfect beach read, if you should be so lucky as to have time at the beach.

Thanks to Julia at The Witcherly Book Company for providing me a copy to review. Which, of course, was not contingent on my actually reviewing it.

Wheels

A woeful number of fantasy readers are unfamiliar with Martha Wells. My proof, you ask? The very fact that rights have reverted back to Wells and she has decided to re-release her books in e-book form. Wide-ranging in world-building and focus, she hasn’t been content to settle down in one fantasy universe and write an endless series (cough, cough, Robert Jordan). I happen to love her fine balance between plotting and world-building, and the way she winds them together with reasonably sophisticated–but non-purplish–language. I’m a little regretful that it took me so long to discover her writing despite my wide-ranging fantasy tastes, and I’d encourage any fantasy reader to check her work out–there’s certainly enough variety that if one book doesn’t suit, there’s likely another that will fit better. And if nothing else, her take on fantasy tends towards the unusual.

Wheel of the Infinite centers on Maskelle, a formerly powerful woman who has left her position as her temple divinity’s living Voice in disgrace. Tet in a society somewhat loosely based on Tibetan Buddhism, there is a pantheon of gods who have spent time on earth and have returned to the Divine Realms. A core ritual of the combined temples is to recreate the mandala pattern of the lands annually or the land will suffer, and this year marks a crucial hundred-year ceremony. Although Maskelle retains many of her powers from her time as the Voice, she’s been traveling incognito, acting as seer for a traveling theater troupe. While looking for herbs, she discovers a river inn overrun with raiders. Feeling rather ornery, she decides to see if there are any honest folk left to rescue, and she instead discovers a foreign traveler captive to the bandits’ amusements. They mutually rescue each other, discovering an immediate connection. He surreptitiously follows as she leads the troupe to the capital city of the Celestial Empire, until a temporary rouse as her bodyguard leads to a permanent association. Once in the city, Maskelle, her new bodyguard Rian, and the troupe quickly become the focus of local politics, both supernatural and corporeal.

As I read, I was strongly reminded of Paladin of Souls, Lois McMaster Bujold’s 2004 award-winning fantasy novel centered around an older woman, long past her enthusiastic and athletic youth. It was clear that Wells had a similar agenda for Wheel, first published in 2000. In an interview at Tor books, Wells states, “for Maskelle I wanted to write about an older woman protagonist because I’d been thinking a lot about the portrayals of older women in books and movies around that time. I’d seen an older movie that dealt explicitly with the idea that when women reach a certain age, we’re just supposed to retire from life, especially any kind of a sex life. So I wanted to write an older woman who was very much still a force in the lives of people around her. I’d already done that with Ravenna in The Element of Fire, but I wanted to get more into it with a main character.”

Are there some problems here? Yes. It didn’t feel like the same polished writing I encountered in Death of the Necromancer, a fast moving 19th century supernatural murder mystery. While I appreciated the nominally non-Western focus and the general female equality, the world-building wasn’t as sophisticated as in The City of Bones. The relationship between Maskelle and Rian was rather predictable and not especially well developed, but I did enjoy the easy way they related without a lot of interpersonal strife. I enjoyed Maskelle’s snarky voice, although I wasn’t entirely sure it was culturally congruent until much farther along in the story. Wheel‘s plotting moves quickly, the characterization is decent, the romance enjoyable without overwhelming the main story and the ending was truly unpredictable. The inclusion and characterization of the theater troupe was a particularly strong aspect, especially the indirect commentary on the role of theater in the community. And the puppets!

Overall, I enjoyed the read, pleased I was exposed to yet another strong entry in Well’s interesting body of work. If you are considering it, check out the first chapter at her site.

I'm not exaggerating--it's fabulous.

Allie Brosh astounds me. Despite her strange little drawings, particularly a self-portrait that looks something like a marine tube worm, she reaches some profound truths in the course of her book. Part graphic novel, part autobiography, she manages to both amuse and discomfort the reader in the best of ways. Though she presents herself as a person struggling with severe depression issues in a number of the stories, she touches on human truths most of us experience.

Hyperbole and a Half originates from her wildly popular blog of the same name (link to her site). Satisfying on a laptop screen, I enjoyed the paper version even more. Made of heavy paper, each section has a different colored page background, making it look a little like a stack of heavy construction paper from the side. It’s a pleasing way to highlight a change in topics. Subjects range from childhood experiences to struggles with her dogs to self-identity and depression. “Dinosaur (the Goose story)” created laughing out loud moments with great pictures. I confess, “The God of Cake” is one of my favorite stories, precisely because I can completely relate. I too have schemed obsessively to get cake, and that tell-tale smear of pink icing at the corner of the mouth–priceless.

The series showing the progressive cake-induced hyperglycemia are hysterical in their accuracy: the dilated eyes, the slightly glazed expression, the dance of sugary joy, the expansive smile…

The God of Cake

Contrast her little pink self with the attention to detail when drawing her ‘special dog.’ The detail in the coat is a great contrast to the solid Colorforms of her characters. And if you have a dog, you must recognize this pose of confused submission:

“Dog” by Allie Brosh. http://hyperboleandahalf.blogspot.com/2010/07/dog.html

I love her humor, her truths, her candidness in sharing some of the awful times of her life, and for being genuine with it, not merely going for laughs–although there are plenty of those. There is an incident during her depression where she relates how she is lying on the floor and discovers a piece of corn under the fridge. It is a perfect example of relating how she experienced that moment, without going for laughs. It is absurd, poignant, honest, and a little uncomfortable. And she leaves it there. Brave choice.

I confess, this is rather what I was hoping for when I read Jenny Lawson’s semi-autobiography, Let’s Pretend This Never Happened. With her strange little drawings and her frankness about isolation and emotions, Brosh won a spot in my heart. Rather entranced by her blog, I decided to order her book as a way of support, despite a space-challenged library. I encourage anyone who follows her to do the same, so you can have a lasting copy of her work.

Known Devil.

With Hard Dark, I had the impression Gustainis was having fun. Enjoying the hell out of himself, in fact, and the enthusiasm translated to an entertaining read. This time, the writing feels forced, rote instead of fun. World-building, characterization and writing all left me left me wishing I had picked up my academic reading instead.

The third installment in the Occult Crimes Unit series begins in a local diner where Detective Sergeant Stan Markowski and his partner, Karl Renfer, are having a coffee break–or blood break in Karl’s case. Karl’s musings on the latest James Bond flick are interrupted by a pair of elves holding up the patrons. The elves are behaving like strung-out drug addicts, but everyone knows supernaturals can’t get addicted to drugs, with the exception of those pesky goblins and their meth problem. Unfortunately, Renfer and Mark are about to discover a new drug that works on supes has made its way to Stanton. Before they can follow-up, they’re diverted to a mass shooting where members of a local vampire crime family are permanently dead, murdered by an out of town gang moving in on their territory. A supernatural drug, a local gang war, and the growth of the local Patriot Party all add up to trouble. Could they possibly be connected?

As a bit of background, while there isn’t anything new or surprising about the world Gustainis has created (unless you count the alternate history that includes Steinbeck writing Of Elves and Men), it’s been largely serviceable world-building. Normally, if world-building isn’t particularly unique, I focus on character or plotting, but alas–the same cut-and-paste from genre tropes is apparent. Stan Sipowitcz as detective. Impaired but recovering relationship with daughter as well as partner. New drug moving into the city causing gang war. Supernatural discrimination. Not-so-shadowy figure who wants to incite a cultural revolution. Stan’s willingness to be jury and judge with lawbreakers.

I wasn’t offended by Detective Stan’s flirtation with the judgmental side of defending his city. I was, however, offended by the facile characterization–and read absolutely no political implications in my complaints–which relied on copy-n-paste anti-immigrant Tea Party description into the anti-supernatural Patriot Party. Ditto the insertion of every Italian mob stereotype you might remember from Godfather-knock-offs into the vampire mob family (“the devil you know…”).

Even more concerning is the general awkwardness of the writing. Take this fragment from a discussion between Markowski and Castle, the head of the supernaturals:

“‘It may surprise you, detective, but I also have read the works of Mister Ian Fleming. Mostly, I regard them as light entertainment, but sometimes, as in your present example…’ The fingers were drumming again, softly as tears falling on a coffin.”

Or the awkward justification where Markowski admits he lied to his fellow officers, lied to a gang leader, but is willing to tell the police department he was lying if he needs to turn in the gang leader (dizzy yet?). Then the transition after Markowski helpfully summarizes his reasoning and plans for the reader his adult daughter:

“She swirled the remaining liquid in her mug and studied the little whirlpool that resulted. ‘This cop stuff gets pretty complicated sometimes, doesn’t it?’

‘Yeah, but it’s nothing that a master detective like your old man can’t handle.”

Yes, I suppose “this cop stuff” is complicated when you are an author and need your character to behave in an uncharacteristic way, but don’t want to re-write everything you’ve done so far.

Then there’s a weird scene thrown in where the department witch does some sympathetic magic, so she kisses our lead. I’d accuse Gustainis of being a bit of a sexist, since the few women characters are only accessories to our lead–except that virtually all the characters are one-note, so it’s hard to say it’s a female-only issue. It is worth noting that when females do appear, Markowski has a definite preoccupation with their sexuality (including his daughter’s, ew).

Quite honestly, I was bored reading, never a good sign. The only reason I didn’t quit was that then I’d have to read three chapters of Study Guide for Understanding Pathophysiology. It was the worst of both worlds; the guilt of procrastination coupled with annoyance at an unsatisfactory diversion. Perhaps I was trying to outwit myself, by selecting a book that would help me study? I like to think so, but I’m afraid I might just be witless.

Not at all transparent

“A quantity of blood is spilled in this story, I’m sorry to say; and a good many people die; and there is some politics too. There is danger and fear. Accordingly I have told his tale in the form of a murder mystery; or to be more precise (and at all costs we must be precise) three, connected murder mysteries.

But I intend to play fair with you, reader, right from the start, or I’m no true Watson. So let me tell everything now, at the beginning, before the story gets going.“

Such a promising beginning; a sly narration, word play, and enticing hints. A troublesome book; very well written, cold and only intellectually interesting characters, dysconjugate plotting, and rather engaging world-building. The result is a book that is clearly well-done but doesn’t ever reach that point of emotional resonance or engagement.

After the prologue by the aforementioned sly narrator, the first section/story, “In the Box,” is about seven men placed on an asteroid as part of their prison sentence. It will be eleven years before the ship returns, so until then, survival is up to them. A fascinating, brutal and uncomfortable character study as the seven men engage in the adult version of Lord of the Flies. The reader knowing that a murder will take place lends an interesting tension to the already violent group dynamics; I was poised on the edge of a reading seat wondering how and when it would happen. Oh, and the ending! A clever, disgusting, squeamish solution.

Onward then, to the next section, titled, “The FTL Murders.” In this section, we are treated to the structure of the 1920s detective novel, with a list of Dramatis Personae. Lead narrator is Diana Argent, an amazingly privileged and gifted young woman with an equally gifted twin sister, Eva. When visiting a world for “a spell of gravity,” someone is found dead. Appointing Iago, her manservant, as Dr. Watson, she regards it as her own personal mystery to solve for her sixteenth birthday. Eva is less interested pursing mysteries, preoccupied with solving an astrophysics puzzle for her thesis. This time, the murder occurs quickly; it is the notorious Jack who is missing from the story. While it was entertaining, it felt more frivolous than the first story, with many accessory characters lending confusion. The FTL, or faster-than-light engine, is introduced and begins to overwhelm the murder mystery. There’s a side emo conflict about unattainable love. At the risk of spoilers, I’ll desist, but suffice it to say, the mystery was alright, I failed to be surprised at Jack’s appearance, and I was thoroughly muddled by the devolution into FTL exploration.

The last section was “The Impossible Gun,” which sort of tied the sections together with a great deal of interplanetary politics (rounding out their beginning in the FTL story), coupled with another murder. More interesting in the general world-building, I had rather burned out on the characters by then.

Roberts’ use of language is frequently wonderful in both expression and concept:

“He’d sat there strapped in his seat…but actually he was hurrying towards his own death. Down to his last few breaths of air. His last hours alive. But he didn’t know!

None of us will know, of course. The weird grammar of death. You die, he or she dies, they die but there is no genuine form for ‘I.’ Not really. All know that, none know when.“

It was partially his skill at language that kept me reading, more than any great fascination with the overarching narrative. No doubt there is lots of Meaning here about humanity, potential, goodness, motive–as well as brutality, rape, and callous disregard of life. But despite enjoying the mysteries, appreciating the writing skill, I found the larger motifs passed me by, and I felt a little like I had closed one of Satre’s stories when I finished. Or quite possible, Vonnegut, but as its been about two decades since I last read him, please don’t take that comparison as fact.

Quite honestly, Jack Glass works rather better if one considers them serial shorts rather than part of a loosely woven coherent tale. But, oh, what a beautiful cover–a stained glass print, bright, cheerful… and deceptive.

14

14

California Dreamin'

You ever have that experience where you finish a book, and are left feeling all discombobulated; not sure exactly what time it is because the sun set while you were reading, and actually kind of hungry because you might have missed dinner? California Bones did that to me.

It wasn’t an instant draw; it had blipped across my radar long enough to make it onto my TBR list, but it wasn’t until bookaneer’s review that I was motivated it to move it up. I picked it up from the library and was sucked into its pages until a solid two hours later. Unbelievably good, it was a breath of fresh air–the forceful Southern California Santa Anas, perhaps–blowing away an urban fantasy landscape cluttered with vampires and werewolves. Van Eekhout combined an almost-now Los Angeles with fast-paced heist, built it on the foundation of serious family drama, added an upbringing in a thieves’ gang, and wrapped the whole thing in some of the more interesting magic I’ve read in years.

“‘Our bodies are cauldrons,’ he said, ‘and we become the magic we consume.’ He often said things like that, things that circled around the perimeter of Daniel’s understanding, sometimes veering just within reach before darting away into ever-widening orbits. Daniel could remember the names of osteomantic creatures and their properties–mastodon for strength, griffin for speed and flight, basilisk for venom–but he grew lost when Sebastian spoke of the root concepts of magic.“

The story begins with a quick flashback to Daniel Blackhand’s childhood, learning magic from his father Sebastian; then forward to a powerful moment his family is ripped apart by the Hierarch; and then a third jump into current time with Daniel working the open-air market. He lands from one frying pan into another fire, only to be offered the ultimate thieves’ job, complete with the opportunity to recover a very personal item. At the same time, Gabriel, a bureaucrat and minor relative of the Hierarch, has the sense something of unfamiliar magic and is troubled that some of the city powers are starting to talk of sedition. When he meets the handler and dog who were chasing Daniel in the market, it sets him on Daniel’s trail, and brings an unexpected chance to confront his own past.

The writing is enjoyable; fast paced, descriptive enough to cause a vivid image or two but never lingering too long, naval gazing at the scenery (I’m talking to you, Way of Kings). An almost perfect tone for the story, it waxes a bit lyrical when describing the magic of osteomancy in all its grim, powerful, glory. I found the degree to which Van Eekhout could make the The Hierarch and his six underlings menacing remarkable, despite their rare appearance.

I liked characterization of Daniel, an ambivalent hero who is mostly trying to keep his head down after the destruction of his childhood. Gabriel is an interesting foil, essentially using the same strategy within the Hierarch’s organization. Side characters are fleshed out enough, and the fact that they are able to still surprised Daniel seems entirely possible. I rather enjoyed Emma and Max, who each played rather interesting sidekick roles to Daniel and Gabriel.

Plotting is quick and ultimately, contained a few unexpected twists. The heist is great fun at the beginning, the standard untouchable target. If it also employs a standard set-up of recruiting the team and planning for the gauntlet, at least it comes complete with humor:

“Emma Walker had observed this routine for three consecutive weekdays before fishing his coffee cup from the trash and identifying the contents of his flask: tequila.

Who the hell put tequila in their coffee? It was disgusting and obscene, and it made everyone on the crew feel better about what they were going to do to Sergeant Ballpeen.“

During the heist, crew member Emma takes a moment to wax poetic:

“‘All my being,’ Emma whispered, ‘like him whom the Numidian seps did thaw into a dew with poison, is dissolved, sinking through its foundations.’

‘That’s from a poem,’ she said with some despair to the crew’s stupefied expressions.

‘Yeah, Shelley,’ Moth said. ‘It’s just we usually don’t do poetry during jobs.’“

The humor nicely contrasts the dark feel of the osteomantic magic, and the compromising situations the team members find themselves in. At the moment, the first three chapters are available for free on Van Eekhout’s website. I highly suggest you give them a try. All in all, it really worked for me, and I’m looking forward to immersing myself a second time–and eventually adding it to the paper collection.

The Martian

“Things didn’t go exactly as planned, but I’m not dead, so it’s a win.“

Mark Watney’s wry evaluation is essentially the summation of his attempts to survive on Mars. After a devastating and unexpected Martian hurricane-force storm wrecks havoc on the Martian crew, NASA calls for an ‘abort mission.’ As Mark is heading to the vehicle that will provide escape from Mars and return the crew to earth, he’s impaled by flying debris, loses consciousness and is presumed dead as the object impaled his suit bio-computer. Ironically, his injury was caused by a piece of antenna that would have enabled him to let his team–or Earth–know he was still alive. What follows is Mark’s log entry of his strategies to survive on Mars and signal Earth that he is still alive.

I tend to avoid most ‘serious’ Hollywood movies because the emotional manipulation is so overt. For similar reasons, I was hesitant to pick up The Martian. A man abandoned on Mars? Cue scenes of astronaut training, sobbing family, distance camera shots of the Earth marble from Mars. But Weir did something interesting, and instead of heading for the maudlin center of a man’s isolation, he focused on the technical problem-solving by an intelligent, clever engineer with a juvenile sense of humor.

I was pleased to find that The Martian worked for me, despite a few story-telling bumps. The overall structure has a couple of rocky (get it?) moments, with jumps in time and place. Although the primary story is taken from Mark’s mission logs, there are scenes centered on NASA as well as Mark’s crew members. One flashback of the crew felt particularly misplaced, but will undoubtedly fit right into the movie version. In terms of language, Mark’s voice is colloquial, and even when he’s talking science and engineering, his problem-solving relatively understandable for the reader. Mark’s skills and necessary solutions draw upon experience in botany, Morse code, computers, plumbing, chemistry, balancing loads, ramp-building–there’s likely something here most people can relate to:

“Problem is (follow me closely here, the science is pretty complicated), if I cut a hole in the Hab, the air won’t stay inside anymore.“

There’s even some science humor sprinkled in among the poop jokes:

“All my brilliant plans foiled by thermodynamics. Damn you, Entropy.“

What really sold me was Mark’s humor, as well as the focus on survival in an unusual environment. There’s a running joke regarding his attempts to entertain himself, only somewhat relieved after rooting through his crewmates’ possessions and discovering data discs filled with 70s memorabilia. Another ongoing gag centers on being the only human on Mars. Instead of despairing, Mark cracks jokes. It felt believable, an almost required personality trait for one of those daredevils we call ‘astronauts,’ and a very adaptive way of coping in small group situations. For some, the lack of overt emotional exploration might disappoint, but it worked well both to off-set the technical aspects, and to avoid the trope-ridden isolation angst. He does let a couple of moments of isolation and frustration shine through, more moving because of how rare they are.

It’s a solid four stars, and clearly headed towards movie status. An enjoyable, quick read instead of the emotional existential tear-jerker I was expecting, with a positive message about humanity. However, when the movie version is finally made, I won’t need to see it–I’ve already seen Castaway and The Terminal. Adding Apollo 13 is unnecessary.

Kindred. We are all kin.

Octavia Butler amazes me. She writes science fiction that is full of complicated ideas about race and sexuality that are completely readable. I’ll innocently start reading, thinking only to get a solid start on the book, and suddenly discover I’m halfway through the story. That isn’t to imply she’s a light-weight, however; her works are emotionally and ethically dense, the subject of numerous high school and college essays. A recent read of Dawn (review) inspired a number of recommendations for Butler and a buddy read of her book Kindred.

The quick summary: Dana is a young woman in Los Angeles moving into a new apartment with her husband when she is suddenly pulled into the past. She saves Rufus, a young red-headed white boy, from drowning, finds herself on the wrong end of a shotgun, and is suddenly returned to home, only to discover mere seconds have passed for her husband. Kevin, also a writer, wants to challenge her story–except that he saw her vanish and reappear three yards away from where she was. As they struggle to understand the where and why, it isn’t long before she is pulled away again–this time to save Rufus from burning his house down. She remains longer this time, discovering she is now in Maryland in the year is 1815, at the plantation home of Rufus’ father, Tom Wylein, and slavery is still a very active practice. The story continues through several more time changes as Dana attempts to understand the reasons for being pulled back in time, her connection to Rufus and her strategies for staying alive as a black woman in 1815.

It sounds rather deceptively simple, but has such emotional and ethical complexity that it is a powerful read. The genesis of the story occurred when Butler was attending Pasadena City College during a time when the Black Power Movement was very popular. She heard a young black man blaming older black people for “holding us back for so long” because of their servility/acquiescence to dominant white culture. She realized that he lacked historical context for his peoples’ lives and didn’t understand their survival strategies. Kindred was a way to revisit that history and see how a ‘modern’ person could cope with their knowledge and experiences. While she originally envisioned Dana as a male character, she realized that there was no way a man would not be perceived as threatening in that situation, and she couldn’t write realistically without him getting killed, “that sexism, in a sense, worked in her favor” (Callaloo, “An Interview with Octavia E. Butler,” C.Rowell, Winter 1997).

While it is technically science fiction, Kindred is more like a mix of historical fiction and modern fiction, similar to Connie Willis’ Time Traveler (To Say Nothing of the Dog review) series. Butler adeptly avoids a common genre trap, and doesn’t bother explaining the mechanism for time travel. Another successfully avoided trope was disbelief of the protagonist, a technique I appreciated. Many authors allow character to get lost in the self-doubt of an “am I crazy?” reaction, but this focuses on the essence of the experience and identity issues caused by the struggle to survive in 1815. Dealing with a slave plantation means the narrative is strongly focused on race. Interestingly, however, Butler allows the reader to develop a ‘racial-neutral’ character feel for Dana for the first few chapters; it is only when Rufus refers to Dana as a ‘nigger’ that the reader realizes Dana is black. Later, Dana relates how she and Kevin met, leading the reader to the realization that Kevin is white, and the challenges they face as an interracial couple are enormous from one century to the next.

Yet, through all of this, Butler avoids the didactic tone that might alienate a reader. She she explores differences in thinking by recounting Dana and Kevin sharing perceptions, and by developing supporting characters that also have their own point of view on adapting. Unable to demonize Rufus, Dana is pulled both by human empathy and by a more unknown connection and actually can’t write him off if she is to survive–in both 1815 and 1976. The relationships between all the characters were quite complicated, and I appreciated how much it added to the story. I generally shy away from historical fiction and was still absorbed. Butler managed to surprise me a couple of times with the plotting, and her characterization is absolutely human; I suggest reading her on that basis alone. Highly recommended.

Lovely

Retelling something as familiar as a fairy tale can be a risky proposition. In some cases, magic can come out of the details as an author elaborates on a classic. For instance, I happen to love Robin McKinley’s book Beauty, a take on the old tale “Beauty and the Beast.” On the other hand, when she re-told the story again twenty years later in Rose Daughter, I didn’t care for it at all. So I brought few expectations to my reading of The Girls at the Kingfisher Club, a retelling of the fairy tale “The Twelve Dancing Princesses.” To my delight, I found a creative, emotionally complex story that takes the original in an empowering direction.

In most versions of the fairytale “The Twelve Dancing Princesses” (a German version is titled “The Worn-Out Shoes“), the story focuses on a challenge to discover why a king’s twelve daughters wake up in the morning with holes in their shoes (one version here). The king is baffled and frustrated, and offers a reward to anyone who can solve the mystery–but if not, then off with his head. Many have been died after falling asleep during their watch. Before accepting the challenge, a soldier meets an old woman who gives him a magic cloak and warns him not to drink anything from the princesses. After the soldier pretends to fall asleep, the princesses dress, go through a secret passage to an underground lake, row across and through a forest of metallic trees, and spend the night dancing with princes at a ball. As they return, the invisible soldier breaks off a piece of a tree, first silver, then gold. On the last night, he steals a goblet from the ball as proof. When the king demands an accounting, the soldier provides the proof and is rewarded by marrying one of the princesses.

Clearly, the origin story is a complex bit of fairy tale, with princesses that are complicit in the deception, a father who is outside it but cruel with his consequences, and a ordinary man using magical gifts to catch the princesses in their dishonesty. Girls versus their father, a common man versus princes, and duplicity all around.

Valentine takes these elements and heads into a very interesting direction. Twelve girls are growing up in a wealthy but isolated household in early Prohibition New York. Rarely permitted outside, or even invited to the downstairs levels of the house to visit their mother, they are ruled by their father in an extremely circumscribed life. Jo, the oldest, has met her mother only a handful of times, and the youngest haven’t met her mother at all. It falls to Jo as the oldest to negotiate on behalf of the sisters with her father. Told in third person limited, largely from Jo’s point of view, Jo ponders her nickname “The General,” arising from the unenviable position as enforcer/mitagator of her father, but yet attempting to protect them against his rage. Unfortunately, her efforts are often underappreciated.

“A ripple of relief ran through the room. It was too loud, too happy; it was a gloss over an unspoken thrum of mutiny so sharp that Jo felt like someone had snapped a rubber band against her wrist.“

Early on, Jo and the second oldest, Lou, would sneak out to the movies where the girls would learn new dances. Natural talents, dancing became a way to escape their limited lives. As each successive sister was delivered upstairs, she was eventually taught to dance by her sisters. In an act of desperation, Jo suggests sneaking out to go dancing–she knows if she doesn’t let the girls blow off steam in some fashion, they might simply run away and be lost forever. The night out dancing is a success, giving the girls hope, a reason to exist and a source of joy and discussion to fill their days. They danced through their nights, unattainable to the men at the clubs:

“The girls were wild for dancing, and nothing else. No hearts beat underneath those thin, bright dresses. They laughed like glass.“

Trouble begins on two fronts when their father decides to actively intrude in their lives. As he schemes to marry the girls off, he gets wind of stories about a bevy of girls dancing at local speakeasies. An ad in the newspaper strikes fear in Jo as soon as she learns of his plans.

“The girls could hope that these husbands, wherever her father planned to find them, would be kinder and more liberal men than he was. But the sort of man who wanted a girl who’d never been out in the world was the sort whose wife would stay at home in bed and try to produce heirs until she died from it.“

The last section follows the girls as they discover life outside their father’s house. I rather enjoyed that Valentine took her story a step beyond the simple “they escaped and they all lived happily ever after,” and looked at the challenges of making a life, and how different the idea of success could be for each sister.

“She was still trying to discover how people related to each other, and how you met the world when you weren’t trying to hide something from someone. It was a lesson slow in coming.“

As in all fairy tales, characters exist largely as archetypes. With twelve sisters, it’s hard to achieve a great deal of individuality with each, but Valentine succeeds with a few, particularly Jo, Lou (the second oldest), and Doris (the sensible one). I thought Jo’s emotional dilemma was well done. The father is perfect; elegant, controlling, and all implied threat.

The setting of New York during Prohibition was nicely done. I’ve read a number of books that were quite enamored of the 1920s, but focused on the setting at the expense of character. Valentine achieves a nice balance between the magic of the clubs and plotting. My chief complaint was a writing style that felt awkward. Additional thoughts and commentary were often given in parenthesis, and the purpose/voice weren’t always clear. Nonetheless, I enjoyed the way Valentine’s tone and word choice was able to capture the emotional magic of a fairy tale but incorporate it into a real-world setting.

Overall, I’d call it a delightful improvement on the original tale. I’d highly recommend it to fans of fairy-tales, sister bonds, coming of age stories and gentle romance.

Thanks to NetGalley and Atria books for providing me an advance ereader copy. Quotes are taken from a galley copy and are subject to change in the published edition. Still, I think it gives a flavor of the magical writing.

A Dragon's Path

I cut my reading teeth on fantasy and science fiction. A regular at the local library, I had gone through their “SF/F” offerings by early teens (which is how I came to read The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant) and relied on my babysitting money and the local Waldenbooks for more current fare. The scarcity of material meant I re-read books I owned many, many times. As a result, when I encounter something that feels new in fantasy, that has a fresh take or inspired writing, I tend to gush (in case you are wondering, both N.K. Jemisin’s The Killing Moon and Frances Hardinger’s Fly By Night were dazzling takes on the genre). I was intrigued with the positive buzz about Abraham’s epic fantasy The Dragon’s Path and had it on my radar for some time. Unfortunately, it felt surprisingly familiar.

This feels like a self-consciousness book. You know; the kind of book that clearly started with a Big Idea instead of a great story. Abraham has both writing experience and Notable Writing Connections around him, and The Dragon’s Path feels like a genre idea in search of storytelling finesse. In fact, in an afterward interview, Abraham mentions that this book was his foray into a full-length Epic Fantasy. Had it been less self-conscious, or integrated better, or maybe had I just been generally new to the fantasy reading experience, I might have enjoyed it more.

There are four viewpoints in the story along with a fifth character who appears in the prologue and final act. Two viewpoints in the story intertwine early on: Marcus, a former elite soldier turned mercenary, and Cithrin, a half-blood orphan ward of a banking house. Then there are the separate stories of Geder, minor noble and sometime scholar, and Dawson, childhood friend of the king and a highly ranked Baron. They mostly start in the city of Vanai, Marcus trying to get free of likely conscription and Cithrin sent out with a wagon from the banker’s house in the last caravan to leave the city. Geder is experiencing his first campaign and discovering it isn’t nearly as awe-inspiring as the written stories. Dawson is scheming against another Baron in an attempt to spur the king to action. Marcus and Dawson are both experienced while Cithrin and Geder are naive and undergoing journeys of self-discovery. Overall, I enjoyed the characterization. While certainly genre typical, they feel rounded enough to be enjoyable. I was interested in Cithrin’s maturation, and the way the traveling troupe took her under their wing. Marcus was admirable but predictable as the heroic archetype (complete with dead wife and child), and Geder the bumbling youth that gets his chance at power.

A few reviewers make a point of remarking on the uniqueness of Cithrin’s role as female financier and the role of economics in the story, but I confess, I was strongly reminded of Silk in David Eddings’ The Belgariad series and his frequent lectures and demonstrations of the economics of trade and the psychology behind business strategies. Quite honestly, it felt familiar–although still enjoyable. While I respect the idea that Abraham wanted the perspective of the individual as he explores the path to war, changing from four different story lines presents a world-building challenge that doesn’t ever quite resolve. There are the Free Cities, each with their own political history; the Severed Throne, it’s rival and their political intrigue; and twelve different races. I got the sense that certain events were supposed to be significant, but I rather lacked the context to understand why. Dawson’s plot line with complicated scheming meant to oppose other factions was particularly challenging to follow.

One aspect that sets Abraham apart are are moments of lovely writing:

“It was an evil that the city would weather, as it had before, and no one expected the disaster would come to them in particular. The soul of the city could be summarized with a shrug.”

“‘Good,’ Lerer Palliako said. He was hardly more than a shadow against a shadow, except that the starlight caught his eyes. ‘That’s my good boy.’“

A reviewer I admire mentions that it is one of the few books she re-read, and felt like a re-read was worth it for the extra understanding, once the reader has the general world-sense. I don’t doubt that. The trouble is, I’m no longer a 12 year old limited to the small fantasy section of the local library and my local bookstore. I can barely find time to re-read the few books I feel were excellent the first time around. I have no doubt that a re-read will give me more insight into the dynamics between the races, and the politics behind the Severed Throne–I’m just not sure I care. But I think Abraham will have a great epic for a new generation of fantasy readers to cut their teeth on.

15

15

Recommended for fans of sci-fi, aliens

Recommended for fans of sci-fi, aliens4 stars for personal enjoyment, 5 stars for quality

As one of the earliest African-American female science fiction writers, Octavia Butler is a must for anyone who reads sci-fi. Fourteen of her works were nominated for the Locus Award during her career, including each book in the Xenogenesis series, but she only had one win, the novelette “Bloodchild.” Dawn is the first book in the Xenogenesis series, published in 1987, and is a science fiction classic. It achieves what the best in science fiction has to offer: by looking at humanity’s interaction with an alien species, it examines what it means to be human and to be emotionally intimate. It’s a powerful story, uncomfortable in character and theme, and yet I can’t recommend it enough.

Lilith is an African-American woman Awakening from a prolonged, artificial sleep. As she reviews her situation, the reader learns humanity was engaged in a full-scale nuclear war that left almost no survivors. Since then, she has been trapped in a white box of a room with virtually no outside stimuli except mysterious voices occasionally asking questions. When Lilith finally meets her captors, she discovers they are humanoid-appearing aliens called Oankali with a talent for gene manipulation, and, even more intimidating, sport a large assortment of tentacles instead of hair. They carefully explain they’ve managed to save the few remaining humans–for the price of some genetic material. Lilith is given little choice to grow comfortable with the Oankali unless she wants to spend the rest of her very long life on their ship. If she can work with them, there’s a chance she can return to Earth.

Divided into four sections, “Womb,” “Family,” “Nursery,” “The Training Floor,” the narrative largely divides the story into chunks of time and stages in Lilith’s interaction with the Oankali. Transitions between the sections seem slightly awkward, sometimes with setting changes, sometimes with significant time breaks. The third person limited point of view brings the reader closer to Lilith’s experience without unnecessary breaks in point of view. Readers who are used to the popular first person perspective, or multi-person perspective may find it hard to emotionally relate to Lilith as she copes with her confinement and the proposed genetic destruction of the human race.

The first time I read it, I was much younger, and lacked compassion for Lilith. She is a frustrating main character who is often focused on opposition without logical basis. This time, I felt I understood her better, although I remained disappointed in her naivete. Butler did an excellent job characterizing the Oankali; I got the sense of an alien motivation, patience and decision-making process while still feeling they were somewhat identifiable. It really is remarkable how few writers are really able to convey a sense of Other; so many times aliens feel like humans dressed up in strange skins. Sadly, Butler also represents the range of humanity including uncomfortable extremes, and it was tough to witness the very real human dynamics.

There is little doubt in my mind that the story of Lilith exploring issues of freedom and sexuality with aliens has a parallel to the experience of the African slave among white slaveholders, or even dominant modern white culture. What does it meant to be genetically pure? To grant humanity to the oppressor? The Oankali are ‘saving’ humanity despite (some) human objection and doing it on their terms. While the Oankali claim their culture is egalitarian and preferable to humanity’s propensity for hierarchy and war, it is clear to Lilith that the third-sex ooloi enjoy a special rank among the Oankali, and that the Oankali are patronizing her and other humans. It is easy to be ‘benevolent’ when they hold the power over human life and death. Essentially, Lilith is given a choice to assimilate or die shipbound, but when she elects to die, the Oankali claim that they know what she really wants, even as she states otherwise. And yet there is nothing simplistic here; it is not merely a case of returning humanity to Earth and letting them recreate their self-destruction. There humans and Oankali trying to do the best as they understand it with a challenging situation.

It is a powerful, uncomfortable story on many levels. The series was released as “Lilith’s Brood,” and in a Youtube promotional video, Samuel Delany said “you read it, you walk around the next few days thinking about it, which is, I think, what good writing makes you do” (“Octavia Butler Profile Piece“). I wholeheartedly agree, which is why I’ll take a breather before advancing to the next in the series, Adulthood Rites.

With some series, you fall in love with the main characters. Watch with interest as they confront their problems, admire their decisions, root for them during lows, and celebrate the victories. Dave Robicheaux is the protagonist in James Lee Burke’s series of the same name, and I’m not particularly sure I like him (Robicheaux, that is, not Burke). I do know one thing, however–I’m in love with Burke’s ability to bring a setting to life. In fact, if Burke ever leaves the mystery gig and heads into travel writing, I’ll be there in a hot minute:

“It has stopped raining now, and the air was clear and cool, the sky dark except for a lighted band of purple clouds low on the western horizon. I drove through the parking lot to the back of the building, the flattened beer cans and wet oyster shells crunching under my tires, and through the big fan humming in the back wall I could hear the zydeco band pounding it out.”

In the fourth installment, Robicheaux has returned to a detective position on the New Iberia, Louisiana police force. Unfortunately, soon after his return, he’s wounded in an incident at work. A hospital stay and prolonged recovery causes a resurgence of post-traumatic stress disorder and he finds memories from Vietnam are invading his thoughts. Even after returning to light duty, he continues to struggle with depression until a friend with the DEA suggests going undercover in a drug sting. Robicheaux takes the job despite misgivings, lured by the opportunity for revenge more than any concern about the federal War on Drugs. The job also gives him a chance to work with his former partner, Cletus Purcel, now running a club in New Orleans. Even more challenging, it means infiltrating the mob and getting information on Tony Cardo, aka Tony the Cutter, a rising wiseguy in the Gulf drug trade.

It’s hard to sum up a plot of a mystery without giving too much away, but suffice to say that this is relatively straightforward. In general, Burke’s plots aren’t particularly formulaic, but there does seem to be a particular pattern of conflict within each book. Robicheaux is largely reactive, driven by his demons and his emotion, and alternates between a more idyllic conflict-free existence in the bayou, periods of active self-destruction and periods of depression. Progress and action on the mystery is driven by either his mood or external forces acting on him. Meanwhile, in his personal life, he eventually finds a woman who represents everything he’s missing and then crashes into disappointment when she fails to live up to his expectations. This particular story isn’t as casually violent as others in the series, although there remain a couple of nicely tense action scenes and one gratuitous Godfather moment. There are a couple of plot points that cause wrinkled brow or stretched credulity, and a B story that isn’t integrated as well as it could have been, so it is slightly less satisfying.

Characterization is stellar. I believe Robicheaux exists somewhere out there, although I’m not sure I’d like to spend significant amounts of time with him. I remain especially disappointed that he is so quick to leave his adopted daughter Alafair with friends or family when he’s following one of his cases. Alafair has had extensive loss–her father likely killed by Contras, her mother dead in a plane accident, her ‘adopted’ mother killed. While Dave recognizes this, he still is driven enough by his obsessions to ignore the consequences to leaving her. It is precisely due to Burke’s skill in characterization that I feel such sympathy, and such frustration. It is also interesting witnessing Robicheaux’s dealings with the black people in the book, as there is a degree of emotional complexity that doesn’t easily boil down to categories. While he has some sympathy for a black prisoner, Tee Beau, and his grandmother, later in the story he is very disrespectful of their belief in a black witch-woman. However, Tee Beau is comfortable calling him out on it, which says something for the quality of their relationship: “In one way you like most white folks, Mr. Dave. You don’t hear what a black man saying to you.” Ultimately, it can be sad and tiring to bear witness for Robicheaux; although he is very human with moments of generosity and kindness, I get the exhausted sense I’ve done this before. Burke doesn’t write mysteries quite as much as he writes an exploration of the human spirit in all its contradictions.

Overall, a solid installment in a detective series exploring inner conflict. I’ve already planned for the next, A Stained White Radiance.

14

14

The other one

Watch out for Martha Wells–I get the feeling she is playing with a different Dungeons and Dragons set than the rest of the world. Rarely has someone in fantasy so consistently impressed me with inventiveness. In City of Bones, she does it again.

City of Bones is set in the city of Charisat, one of the few major cities remaining after an apocalypse has nearly destroyed humanity. Cities are surrounded by a hostile, desert Waste, and survivors rely on the roads of the Ancients to travel from one city to another. In Charisat, Khat, a krisman, and Sagai, a foreign scholar, are bargaining with a relic trader when they are approached by the entourage of a heavily robed but obviously wealthy individual. The group wants guidance to a nearby Ancient Remnant. Of course, Khat has skills as a local expert in Ancient artifacts–but he is all too aware that a kris, he is also expendable. However, there is a debt he’d like to clear and both the guide money and the wealthy patronage could buy him a way out. When the caravan is attacked by pirates in the Waste outside the city, it sets off a chain of complex events that result in Khat working with the mystery person to ‘collect’ two more relics from inside the city of Charisat. The anonymous aristocrat is revealed early on, so I hesitate to say more at the risk of spoilers, but bone prophecies, thievery, the underground market, the academy, ghost spirits–so many elements make this intriguing.

World building is fascinating; no doubt her B.A. in Anthropology has influenced the thoroughness of detail to these societies. There’s a complex cultural mix involved, from the long-dead Ancients to the ‘modern’ survivors, from city residents to Waste-dwellers (rural), high class to untouchable, magic-users and prophets, and even a mix of races/species. Information is parceled out nicely, balanced with action and dialogue. Everyone is working their own angle here, so the possibility of duplicity and lack of shared knowledge keeps suspense high.

“‘He could still be a Trade Inspector trying to trap you somehow,’ Sagai argued as they crossed the court….

‘Then I’ll be honest,’ Khat answered, reaching into the door hole to pop the latch. ‘I’m always honest.’

Sagai snorted. ‘No, you think you’re always honest, and that is not the same thing at all.’”

Characters initially seem to be along somewhat standard stereotypes–Khat is a distrustful but essentially ethical thief, and the aristocrat a somewhat naive but socially and politically powerful magic-user (why hello, Mercedes Lackey). Sagai is nicely done as the level-headed and supportive friend. However, it doesn’t take long before their characters develop unique identities. One of the aspects that I loved was the obvious enthusiasm and reverence Khat, Sagai and others have for the pursuit of knowledge about the Ancients. It reminds me of 19th century explorer-archeologists in Egyptologists who unearthed artifacts to make a living–but also because of the mystery. There’s great little bits of humor as well, particularly from Sagai’s wit:

“‘Why is a clear conscience necessary?’ Sagai asked, not helpfully. ‘All it takes is a confused sense of duty and a disregard for personal survival.’”

One of the fascinating issues is Khat’s identity as a kris. We learn that the Ancients are said to have created them, but details of their secretive society are limited, and justly so, as the magic-using Warders of Charisat are prone to labeling them as ‘souless’ and therefore non-human. Thus, Khat is used to indirectly explore interesting issues about racism and humanity. Khat is also used to invert and explore issues about gender identity. He mentions that he would have been the “second husband” if he stayed in the krismans’ enclave, on the receiving end of all the hard household work and child-rearing. Comments are made by various about his ‘prettiness,’ and the kris’ unusual physiological adaptation means nurturing the young is not a female-only task. Women play a strong active role in this book, at the same level as the men, and its rather refreshing to have characters treated like people instead of gender roles.

I found it an engrossing read satisfying on my favorite fantasy fronts of plotting, characterization and world-building, with complexity in language and ideas. This would be a perfect book for fans of Way of Kings–as well as those like myself who felt Kings lacked action.

Thanks to Mimi for her review, inspiring me to bump it up the TBR pile.

Written and Read

Remember how I said Half-Off Ragnarok was like sugary breakfast cereal? This is sheer milk chocolate candy addictiveness–the M&M kind–where you think “sure, I’ll have a couple,” and then it’s a couple more, and then just a few more, and suddenly the bag is half gone. Written in Red is melt-in-your-mouth goodness targeted squarely at the urban fantasy-paranormal fan whose appeal is intensified by a couple of surprising features. It was so very readable, going down exactly like those M&Ms; before I knew it, it was 3 am and I was almost done. Kudos, Bishop, kudos.

A brief prologue orients the reader to the history of the Others, the indigenous spirits of the world, and of humans. At creation, humans were given isolation to learn and grow, but as they spread throughout the world, they encountered the Others. Humans and Others skirmished, with humans largely on the losing side as the Others control natural resources. Currently, they have forged an uneasy peace, with the Others maintaining compounds in some larger human towns and cities, much like diplomatic enclaves.

The first chapter starts in the city of Lakeland, with Meg on the run during a snowy night. She sees a sign at the Other compound requesting applications for a human liaison, and realizes this could mean freedom from her prior life, as human law doesn’t apply in Other territory. Samuel, dominant wolf and leader of the compound, is vaguely troubled by Meg but gives her the job–after all, they could always eat her. Quickly installed in the Liaison’s apartment, Meg soon begins learning about the Others…as well as herself. Interwoven with Meg’s story, the narrative also follows Asia, a human woman scheming to learn more about Samuel and the Others; and Lt. Montgomery, a recently transferred police officer who takes on the role of ambassador for the department with the Others.

The creation of a supernatural/mystical creature dominant world is one of the most interesting aspects of Bishop’s world-building. I found myself fascinated by the idea of an alternate-history universe where we have many of the same things (cars, sneakers, bagels, chick-flicks), the same rough geographic layout (the Atlantik Ocean, the Great Lakes) but with the threat of the Others looming in the everyday background. For instance, it isn’t long before Monty learns that the the legend of the Drowned City is actually true–a human uprising in the area was punished by a massive flood.

Characterization was acceptable, if rather standard for the genre. Because of Meg’s ability to make predictions through cutting herself, she had a heavily circumscribed upbringing that prevented exposure to the outside world. Thus we have the standard naive young woman who possesses ‘book’ knowledge without ‘street’ knowledge with a highly valuable (magical) skill-set. Bishop’s choice to use blood prophecy was inspired, particularly as ‘cutting’ is a taboo real-world issue. Meg does develop as she struggles with agency, particularly as she starts to understand more about her own abilities. Likewise, the elemental spirits were well conceptualized, with a sense of indifference to consequences and a selfish focus on their own interests. Tess was one of my favorites of the Others, with her moody hair and mysterious identity. However, Samuel mostly seemed angry and conflicted, and rarely gave the sense of a confident, focused personality that one might expect as leader of a large, dynamic group. Likewise, while the vampires initially gave a feel of spine-chilling fearfulness, any efforts in that direction were completely undermined when one of them asked Meg is it was “that time of the month?” Truly, by the end, they did seem a little like television vampires, perhaps because of their own obsession watching it. The two other narrative viewpoints of Monty and Asia were also very straightforward. The police officer might as well have been called Trueheart, and Asia was a one-note scheming narcissist.

Actually, what has been perplexing me is that in the wrong mood, I might have easily hated this book. The language is relatively unsophisticated and dialogue-focused. The plot turned out to be predictable–my tension reading was out of concern that Bishop, as a writer new to me, might come up with unpleasant surprises, but there weren’t any. I could probably make a couple of educated guesses at the next book as well. There’s also the larger issue of Samuel’s tendency towards violence, anger and possessiveness. I think he comes off as more combative narcissist than ‘wolf,’ and more disturbed human than ‘Other,’ no matter how many times he mentions the need to be in his “other skin.” Gender, identity and sexuality are all very straight (literally), with Meg and Tess the only unknowns in the story. Plotwise, Bishop is clearly setting up the beginnings of a romance, but not until Meg learns her own dominance. And Meg is one marvelous, Speshul Snowflake. To meet her is to love her, apparently. For a lot of reasons, this could have gone the other way.

But the marvel was it didn’t. I devoured the book in one sitting, expected plot, Speshul Snowflakes, anger issues and all. I can only conclude that Bishop is meeting my genre expectations so well, with that flair of intriguing difference, that it was irresistible. In fact, when I finished, I was seriously spent a couple of minutes debating whether I should download the next book on Kindle and keep reading. It was only discovering that only the first and second books are out, with book three not expected until March 2015 (and four and five in the works) that kept me from an all-night reading binge. So I re-read it instead.

Hook me up and pass the M&Ms, please.

22

22

1

1